Large Behavioral Models

A Foundation Model Paradigm for Human Actions

PDF

First circulated privately on July 26, 2025.

Foundation models have achieved remarkable success by learning from large-scale, unstructured data in domains such as language, vision, and genomics. Yet an often-overlooked source of massive, rich information is behavioral data: the discrete actions, transactions, and interaction logs generated by billions of users across sectors including retail, payments, app usage, and workforce management. We define a new paradigm where user actions define meaning in a manner complementary and often orthogonal to the semantics captured by Large Language Models (LLMs) and Large Vision Models (LVMs). We instantiate this approach with BehaviorGPT, a frontier LBM that exhibits strong zero-shot capabilities. In real-world trials with leading enterprise partners, BehaviorGPT improves predictive accuracy and decision-making, including double-digit sales uplift for retailers and payment companies. Our findings underscore the untapped potential of action-centric training for enterprise applications and highlight the importance of integrating language-based and behavior-based intelligence for more robust, general-purpose AI. Models can be accessed via request at www.unboxai.com.

Foundation models [1]—large-scale models pretrained on vast datasets to acquire general capabilities, which can then be fine-tuned or prompted for downstream tasks—have achieved remarkable success in domains such as language, vision, and genomics. In this work, we extend this paradigm to the realm of human behavior, focusing on discrete action spaces in areas like transactions, retail, app usage, and workforce dynamics, with particular emphasis on retail and consumption patterns [2, 3, 4]. Our approach also reveals emergent capabilities for a broader range of behaviors, hinting at potential for general intelligence. We present lessons from BehaviorGPT, a sequence of Large Behavioral Model (LBM) generations that exhibit strong zero-shot performance. In real-world deployments with leading retailers and payment companies, they have driven double-digit increases in sales.

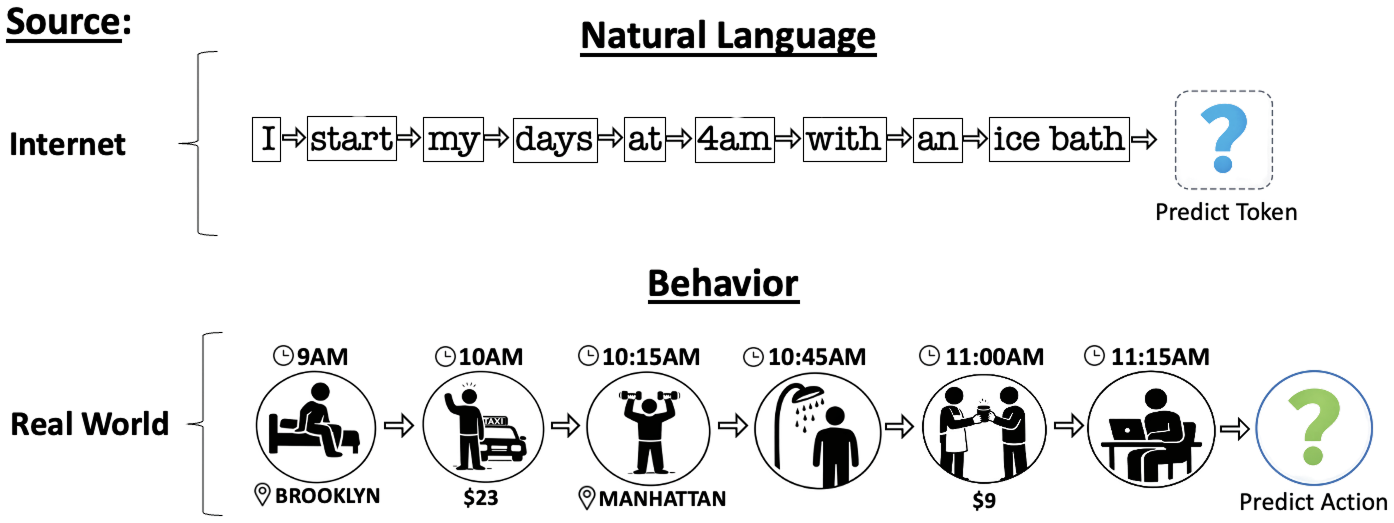

The maxim "actions speak louder than words" carries significant implications for artificial intelligence (AI), even in the context of advancing toward artificial general intelligence (AGI). Large Language Models (LLMs) model language as sequences of words or tokens, using autoregressive next-token prediction on internet-sourced data. Similarly, we model behavior by collecting an individual's actions, ordering them chronologically to form sequences, and training via next-action prediction (see ). This enables the model to learn the "language" of human behavior. While textual understanding from the internet is essential for tasks like drafting an email, behavioral understanding is critical for planning your day (simulating human reality) or recommending actions.

As internet text data becomes increasingly scarce for training, behavioral data offers a vast complementary source. Estimates we conducted with major data providers suggest that behavioral data in retail and payments alone may exceed internet text data by a factor of 100–1000. Much of the information individuals and societies generate is non-textual and offline, yet it is rich, vital, and often more honest—reflecting actual actions and decisions rather than selectively shared content. It is hard to imagine a reliable and optimal AGI that has not been trained to understand this data, as it is essential for comprehending the full human experience. Indeed, as detailed in this paper, we find that behavioral data proves significantly more predictive than internet text for many tasks and contributes to models that are not only plausible but accurate.

For behavior-driven domains and businesses, behavioral data is not merely a nice-to-have or an enabler for aspirational AGI, but fundamental and essential to leverage. For retailers, for instance, the ability to recommend the right product to the right user at the right time encapsulates their core business intelligence and should permeate all operations. Similarly, for many enterprises, predicting optimal actions for users at precise moments defines their competitive edge with the key question being what those actions entail. In behavior-driven industries like retail and payments, over 99% of data is behavioral: inexpensive to collect (via user tracking over time) and highly informative, narrating user preferences through interactions. LLMs have not revolutionized these sectors at their core because their intelligence is text-based, derived from the internet, rather than action-oriented. There is thus a pressing need for a behavior-native foundation model—a "ChatGPT moment" for behavior-driven intelligence—which we believe BehaviorGPT represents. Beyond superior intelligence, a foundation model trained on an enterprise's core behavioral data also breaks the one-model-per-function paradigm, letting companies scale intelligence without scaling complexity, headcount, and operational overhead.

Like other foundation models aspiring toward generalized intelligence, the main challenge is to achieve true generalization. For LBMs, this entails the ability to predict any output action from arbitrary input sequences, without assumptions about format, ordering, or platform-specific constraints. We aim to avoid siloed models (e.g., one for social media recommendations, another for retail fraud detection). This is challenging for actions, which are often platform-dependent, necessitating universal action descriptions rather than one-hot embeddings or SKUs. Prior efforts in behavioral foundation models have been site-specific, lacking the cross-domain generalization our approach achieves.

Roadmap. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 defines Large Behavioral Models and positions BehaviorGPT within this framework. Section 3 offers a non-technical position paper and discussion of BehaviorGPT's implications and key insights from its development and deployment.

Large Behavioral Models (LBMs) sit within the broader class of foundation models: any model trained on broad data (typically via self-supervision at scale) that can be adapted (e.g., fine-tuned) to a wide range of downstream tasks [1]. This foundation is shared with Large Language Models (LLMs) and Vision-Language Models (VLMs), but LBMs diverge in their approach to data interpretation and meaning derivation.

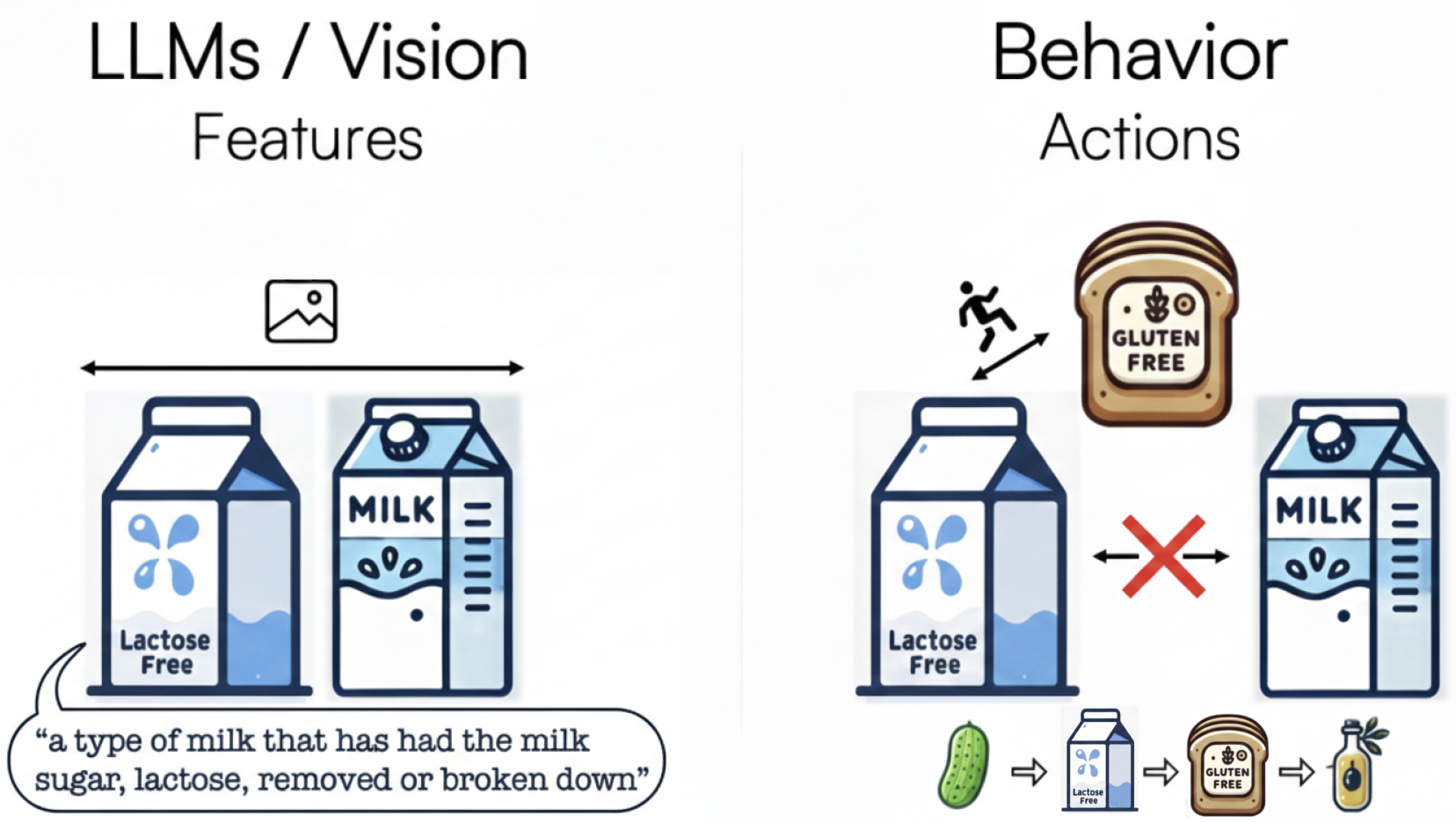

LLMs and VLMs primarily learn from statistical co-occurrences of text and images in contexts like webpages (, left). Here, the meaning of pixels emerges from their co-occurrence with other pixels and surrounding words, while words derive meaning from adjacent text and images. However, webpages represent manufactured artifacts, not chronological behaviors—they are outcomes of actions, often acted upon themselves (, right).

In contrast, the behavioral perspective is dynamic and sequence-oriented. It encompasses two key views: (i) the chronological actions of the creator producing the content (e.g., a webpage), defining elements like pixels and words through their co-occurrence in the creation sequence; and (ii) the chronological actions of users interacting with the content, where meaning arises from co-occurrences in consumption or engagement sequences.

This results in representations distinct from those of LLMs or VLMs. Fundamentally, any text, image, or video rarely represents a chronological sequence of individual human actions; instead, it is the aggregated outcome of those actions across individuals, e.g. consider the iterative process of writing, editing, and refining this very paper, interspersed with pauses and external influences. The underlying actions, rather than an aggregated artifact, represent a different perspective. One that, from a behavioral standpoint, is much more honest.

Importantly, the behavioral lens is not merely an additive layer atop LLMs and VLMs; it introduces a complementary, often orthogonal dimension. Recent advancements in robotics illustrate this: models trained solely on static images or text may misinterpret scenes due to a lack of action context. By contrast, training on video sequences in robotics (behavioral trajectories) enables superior interpretation, as elements are understood through their roles in action flows rather than isolated co-occurrences. Thus, behavioral data provides not just more information, but qualitatively different insights—even averaging all behaviors involving an image typically does not replicate the meanings based on pixel occurrences or online text-image pairs that VLMs and LLMs capture.

Consider the classic "invisible gorilla" experiment: participants tasked with counting basketball passes in a video often fail to notice a gorilla walking through the scene, as the behavioral context of the task filters out irrelevant information rather than merely adding more details; it fundamentally alters perception.

By our definition, LBMs encompass a broad spectrum of behavioral intelligences. One useful categorization is by domain and temporal span. For instance, LBMs in robotics (sometimes called Large Behavior Models) typically focus on short-duration tasks, such as washing dishes or driving a car, involving minutes or hours of high-fidelity, continuous data (e.g., tracking hand positions or sensor readings). In contrast, our work with BehaviorGPT centers on discrete action spaces in domains like purchases, consumption, app usage, and interaction logs—time-series data that span years rather than moments. Over time, these paradigms may converge, leading to greater centralization among LBMs. Indeed, the strong performance of BehaviorGPT demonstrates exceptional transfer learning capabilities across diverse domains and temporal scales.

In summary, LLMs derive meaning from linguistic co-occurrences, LVMs from visual (and textual) co-occurrences, and LBMs from behavioral co-occurrences, forming a triad essential for holistic AI understanding.

What does "milk" mean? Regular milk, lactose-free milk, or perhaps a T-shirt emblazoned with the word "milk"? In an LLM, we rely on contextualization from surrounding text, but in retail search, we expect the AI to intuit user intent. If someone searches for "milk," do they simply want milk, or would they prefer an automated basket fill of their week's worth of groceries, proceeding step-by-step only due to current limitations? Should we surface carrots alongside milk if behavioral patterns indicate that's the next likely item? This might seem unconventional, but if it accelerates basket completion and delights users, why not? In recommendation terms, this blurs cross-selling and up-selling; ultimately, the goal is delivering what users want, when they want it. Similarly, a search for "Caesar salad" might warrant not just salads but also ingredients, further dissolving boundaries.

Behavioral sequences often reveal such patterns:

search: "caesar salad" → search: "romaine lettuce" → product-add-to-cart: "romaine lettuce"

Here, the initial "caesar salad" query likely yielded suboptimal results, prompting a pivot to a specific ingredient. By training an AI to directly suggest "romaine lettuce" for "caesar salad," we enhance the experience based on observed suboptimal behaviors.

Deploying improved search could encourage higher-level queries (e.g., "caesar salad"), capturing richer signals in new data and iteratively refining the system. Thus, AI development and data collection must evolve hand-in-hand: superior AI yields superior data, fostering user freedom and more accurate intent reflection. Start early and iterate often. We term this compounding effect the "interest rate" of foundational AI, estimated here at 2.5% annual revenue growth from re-training and re-deployment alone (excluding gains from new AI-enabled products).

We often approach experiences too abstractly, prioritizing expert sensibilities over user helpfulness. True utility demands deep insight into user intent, not rigid rules from domain experts. There is no objective result for "milk." It varies by user, despite strong opinions on definitions or rankings.

The prioritization of abstract reasonableness over empirical correctness carries over to LLMs and VLMs. Hallucination is a symptom—not just fabricating facts, but reflecting a human tendency to rationalize anything as acceptable. For LLMs and VLMs, it seems reasonable to group regular and lactose-free milk as similar products for recommendations because they share features. Yet, behavioral data reveals they're rarely purchased together; lactose-free milk pairs better with gluten-free bread. For retailers aiming to understand and serve customers, "reasonable" misleads while correctness drives value. See for an illustration.

The repeated experience of this costly lesson has given rise to the saying, actions speak louder than words. Indeed, foundation models like LLMs and VLMs face a fundamental challenge: they rely heavily on internet text, which is secondhand information—loose, biased interpretations of the real world. What we choose to share online is always filtered, often reflecting aspirations rather than reality. The internet is a think-and-talk space, shaped more by how we want things to be than by how they actually are. While online discourse can be persuasive, it is rarely grounded in truth or action. In contrast, observing what people do, rather than what they say, is far more predictive. Yet the internet is overwhelmingly made up of talk, not behavior. As a result, LLMs, trained on this talk, often learn to sound good and reasonable but are frequently wrong, with hallucinations being one form of this failure. This disconnect can have serious consequences and often limits the value these models deliver to enterprises. We believe this helps explain why LLMs have fallen short of their promise to transform entire industries. Interestingly, one area where LLMs have truly excelled is in coding. This is largely because they have been trained on vast amounts of code which offers a rare connection to a verifiable form of reality: code either compiles or it does not.

In contrast, training a Large Behavioral Model directly in the behavioral action space produces models that are significantly less biased, substantially more predictive, and inherently aligned with a behavioral understanding of human activity.

Consider the following "reasonability" efforts:

Reasoning. When we build the reasoning capabilities of LLMs, we train them to use test-time compute to reason in language space. When they need to interact with the real world—i.e., the action space—they rely on external tools (such as web search or UI interaction) through agents. In contrast, BehaviorGPT is trained directly in the action space and can reason within it natively. We use test-time compute for reasoning over behavioral actions, enabling it to traverse, plan, and verify directly in the action space. This allows BehaviorGPT to perform actions like searching or clicking internally, without relying on slow external tools, and makes it well-suited for end-to-end training. As a result, it provides a far more native and efficient way to simulate real-world actions and behaviors. In contrast, LLMs must conjecture about action through language, as they are not trained on or optimized for direct interaction data. In essence, current reasoning methods simulate trajectories in a secondhand reality, based on language and internet text, whereas the more useful approach is to simulate real trajectories in the real world, which is precisely what LBMs are designed to do.

Data analytics. Traditional top-down data analytics is often prone to wishful thinking and distortion, biasing results to fit expectations or desired outcomes. It is overly simplistic, usually highlighting only the factors one is already looking for. A more effective, robust approach is bottom-up: training a large neural network, such as a foundation model, to compress the data, and then prompting or dissecting the model to uncover what it has learned. This method forces the system to contend with all the nuances in the data, leading to multivariate, multidimensional insights that are less dependent on unrealistic assumptions. While there is a growing belief that reasoning LLMs and agents can take over analytics, they largely replicate the same top-down paradigm, just with more complex equations. But this does not fundamentally improve our understanding. In fact, the success of LLMs is proof that traditional analytical methods are limited. The future of data analytics lies in training foundation models and extracting understanding from them—a process that truly advanced reasoning agents will ultimately need to adopt as well.

Agents for everything. While useful, agents are not the full solution. There is far more to human behavior than what internet-trained LLMs capture. They may appear to be reasonable tools in some cases, but often they are not. For example, agents used in cybersecurity to identify malicious bots will never be as effective as an LBM trained on real human behavior. To truly support a human user and provide safe, meaningful recommendations, an agent must deeply understand the person; not just offer rationales that sound right, but ones that genuinely align with their actions. The key question is not simply whether an AI can complete a given task, but whether it can solve that task perfectly for you.

LLMs will not solve problems by going deeper into directions that are inherently futile. That said, LLMs are still powerful and incredibly useful. There is no reason why foundation models like LLMs and LBMs cannot be combined to compensate for each other's shortcomings. We see LLMs as one form of intelligence and LBMs as a complementary, distinct form. Which model does most of the heavy lifting depends on the context. In several successful cases, we've seen BehaviorGPT collaborate with an LLM, where the LLM handles parts of the user interface and contributes text-based reasoning. BehaviorGPT acts as a tool for the LLM, and vice versa. In this setup, BehaviorGPT replaces traditional RAG models and offers much more sophisticated capabilities, giving the LLM deeper insight into user behavior and enabling it to reason about actions and simulations. In fact, we've worked closely with OpenAI on a client project using this approach, offering a promising glimpse into how complementary foundation models can create exciting new capabilities and shape the future of intelligent systems.

Allowing users to define the meaning of things through their actions also enables us to better understand them. In natural language processing and LLMs, the sequences being modeled are sequences of text tokens. A common objective in language understanding is next-token prediction: predicting the next word given the preceding ones. For example, given the phrase "The meaning of," the model might predict "life". The intuition behind this task is that to predict the next word accurately, the model must grasp the meaning of the word, the sentence, the paragraph, and even the full document—purely from the sequence itself. This same intuition can be applied to other types of interaction sequences, such as product purchases by customers or workplace behaviors by employees. To predict a customer's next action, the model must implicitly learn attributes like age, mood, and price sensitivity; for an employee, it might learn factors such as health, sociability, agreeableness, and competitiveness. The core idea is that predicting what someone will do next requires understanding who they are. In this way, we gain insights not only into the structure of the sequences but also into the users they represent.

Once a language model has been trained on a language understanding task (such as next-token prediction) it can be adapted (through fine-tuning or prompted) to perform other tasks like sentiment analysis, question answering, text generation, and search. What we consistently find is that the core language understanding capabilities of the model significantly enhance performance across all these downstream tasks. The same holds true when training models on behavioral data. However, the kind of accuracy and insight gained from behavior models is fundamentally different from what language models provide.

Since LBMs provide a fundamentally different form of intelligence, they should not just add new functionality—they should also challenge and replace outdated assumptions. It is crucial to deploy the right kind of intelligence where it matters most. Many are excited about LLMs and focus on building new chat interfaces, but often overlook the value of leveraging their own data to gain a competitive edge, especially in the channels where the majority of their users actually interact. For example, many retailers neglect to apply their best AI efforts to search and recommendation systems, even though that is where a majority of impact happens. These are also the areas generating the most new behavioral data, and to benefit from the compounding returns of AI, this is where you need to focus and iterate consistently.

Indeed, one of the most compelling reasons to build foundation models on your own data and deploy them in production is the compounding effect they enable. Better solutions generate better behavioral data, and training on that improved data leads to even better models. After running our models in live products for several years, we have estimated what we call the AI-and-data "interest rate": the year-over-year revenue growth achieved simply by retraining and redeploying models on newly collected data. We estimate this compounding return to be around 2.5% annually. Notably, this figure reflects gains from existing solutions alone; it does not account for the revenue potential unlocked by developing entirely new solutions made possible by deeper intelligence or emergent capabilities.

Of course, at some point, increasing the amount of data, compute, or model sophistication just to squeeze out another 2.5% improvement in accuracy may feel like diminishing returns. And in some cases, that is true and then the competitive advantage may no longer lie in traditional performance benchmarks. But this does not mean the underlying intelligence has plateaued. Instead, it often manifests in new and less obvious areas.

For instance, perhaps a recommendation engine is not improving much in terms of click-through rate, but the model may now be sophisticated enough to offer actionable insights about product strategy. It might suggest how to improve product images or descriptions to better appeal to users, or even help identify entirely new products to introduce. A strong model might also generalize across domains. For example, leveraging insights from poster purchases to inform trends in furniture or fashion.

Yes, there may be a ceiling to how good search or recommendations alone can get, especially when trying to optimize the long tail. But that same intelligence can reveal deeper, more valuable understanding: how your business works, how to better present your products, what to launch next, and how to expand into adjacent markets. This is where larger models and richer datasets truly shine, by enabling general intelligence that goes far beyond single-task performance.

This is also why the future of intelligence cannot be fragmented into isolated services. The real competition will not be about who has the best search or recommendation engine per se, it will be about who delivers the most complete and actionable intelligence across their entire business. A system that recommends the right product at the right time to the right customer is not just a recommendation engine; it's a model that understands your business. It knows (at least implicitly) what products to introduce, how to position them, what messaging will resonate, and what else to offer your users. That is the kind of general business intelligence that defines the future—and the advantage will belong to those who build it.

LBMs are not only a complementary and fundamentally different form of intelligence, they also significantly outperform LLMs and VLMs in behavioral settings, all while being much smaller and more cost-effective. This efficiency dramatically expands the practical applicability of foundation models, particularly for businesses operating in behavior-driven domains. As our work shows, foundation models should and can power personalized experiences at every point of interaction between humans and technology. In these contexts, performance should not come at the cost, latency, or scale limitations typical of LLMs, but instead match the efficiency and responsiveness our behavioral models offer. What we demonstrate is a viable path to deploying foundation models at scale. Not just in isolated use cases, but in everyday moments: every scroll on your phone, every visit to a store, every card tap, even every time you grab extra napkins. Ultimately, it becomes a question of return on investment. To reach the Pareto frontier of AI-driven user experience (balancing quality, cost, and speed) these differences matter greatly.

Lastly, we want to emphasize that LBMs are not just a watershed moment for behavior-driven intelligence in retail and payments. They also represent a crucial component in the path toward AGI. While major players continue to focus on text, images, and video, they often overlook the vast volume of behavioral data generated by humans outside traditional online content. LBMs capture a complementary type of intelligence that is largely missing from current datasets and models. This behavioral dimension will likely become increasingly critical on the journey to AGI, perhaps not immediately, but probably sooner than we expect.

For those who believe a superhuman intelligence should primarily use abstract logical reasoning, grounded in game theory or research papers, to infer user intent and behavior by "reasoning through" trillions of actions rather than learning directly from those actions, we think that view is mistaken. Intent is not a clean deductive object; it is an empirical distribution shaped by context, constraints, and habit. Training a model on real longitudinal behavioral trajectories at scale, without importing preconceived notions about what people should do, forces it to internalize reality as it is, much like humans do through lived experience. This is also how the human brain has approached the problem over billions of years of evolution, and we expect a superhuman AGI to do something similar: grounding its understanding in behavior via a specialized "sub-brain" trained on actions, with explicit reasoning layered on top. Reasoning remains valuable, but it should sit on top of this behavioral substrate, not replace it as the primary source of understanding.

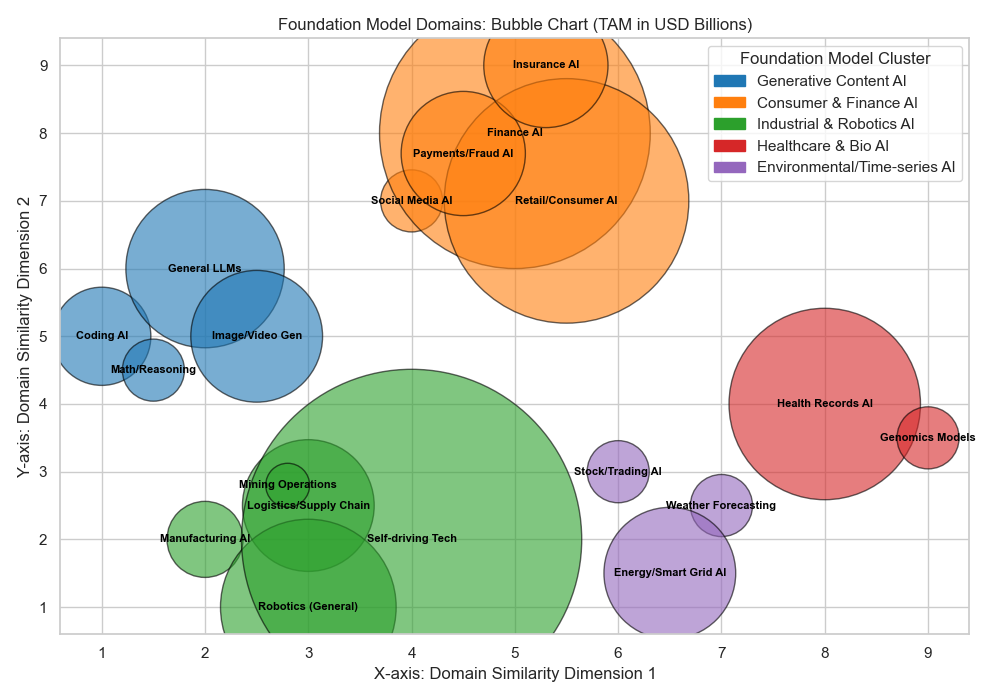

If there will not be a single AI foundation model to rule them all, then which ones will emerge and what will their impact be? Much like the human brain is composed of multiple subsystems that interact with one another, we expect the foundation model landscape to evolve into a network of specialized models, each focused on distinct data types and applications. Just as LLMs and LBMs serve different purposes and reflect different forms of intelligence, we believe this division will persist for the foreseeable future.

What is particularly interesting is how shared foundation models may reshape the definition of industries. Rather than organizing markets by traditional verticals, we may begin to define them based on shared data synergies and collaborative intelligence. In this new paradigm, businesses that share foundational behavioral data may cluster around a common model, blurring conventional market boundaries. See for a visualization of shared market structures and their total addressable markets (TAM).

We have already explored a range of high-impact applications for BehaviorGPT, including:

We articulated this in 2018 at the outset of our project, and it has since proven to be surprisingly accurate:

We care about building a single core model of understanding for a company. We think many functions that define important concepts (such a human behavior) are functions of time, and can be seen as sequential. This coupled with the advances of sequential processing and unsupervised sequential objectives allows for a systematic and general approach for many settings. The generality of sequences and relating unsupervised objectives (such as predict-next-event) allow us to pool all data surrounding a company into dataset consisting of sequences. The idea being interaction consists of agents (the one that acts) and an item (the one being acted upon); and the best way to understand both agents and items is through these sequences of interaction. I.e. an agent is defined by how it acts on items, and items are defined by how they are acted on by agents. We strongly believe that focus should lie in building a good model for the core understanding of agents and items, because it will be helpful in any application where either agents or items are involved; all such applications should be seen as downstream or finetuning tasks, rather than problems that should be attacked in isolation. Ultimately, we believe that one market, to the extent that it can be defined, should be defined by strong synergy effects and related behavior, thus training a single model successfully on all the market's data achieve superior performance and will be best positioned to grab that market.

Since then, we have shipped a sequence of BehaviorGPT generations, each building on the previous one, in collaboration with leading companies. Along the way, we have seen scaling laws materialize in practice and accelerated toward what we believe will be a near-term inflection point for Large Behavioral Models.

We thank our enterprise and SMB partners for their collaboration, domain expertise, and feedback throughout this project. We are grateful to work with organizations ranging from Fortune 50 companies to small and medium-sized businesses across diverse behavior-driven domains. We also thank the teams and individuals who supported data engineering, deployment, evaluation, and product integration. Finally, we thank current and former Unbox AI employees, advisors, and friends for their contributions and support.

@article{unbox2026lbm,

author = {Rickard {Br{\"u}el Gabrielsson}},

title = {Large Behavioral Models: A Foundation Model Paradigm for Human Actions},

journal = {Unbox AI Blog},

year = {2026},

month = feb,

url = {https://research.unboxai.com/large-behavioral-models.html},

}